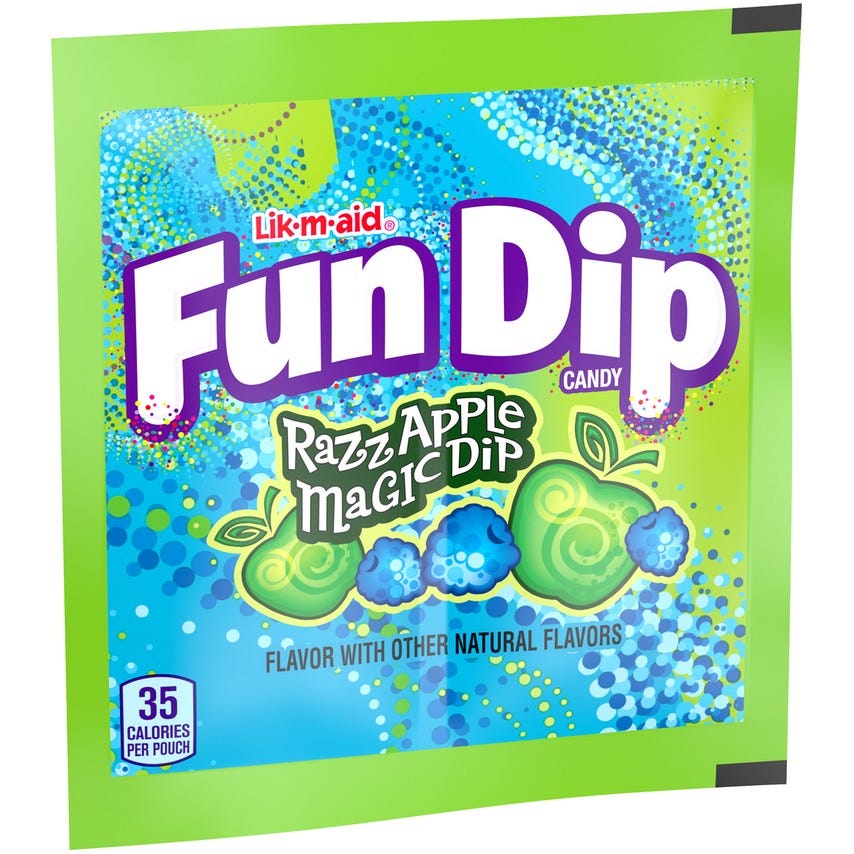

Fun Dip

My son’s Valentine’s candy triggered a painful memory that ambushed me this week. That memory, his reaction, and when past is neither prologue nor even really past.

After twenty years of marriage, there is no greater chasm that separates me from my beloved than the fact that she has an intense sweet tooth, whereas to me sugary candy tastes like the sickly, sticky, treacly tendrils of a lesser devil. It’s not the most revolting thing to eat in this world—Behold the Aubergine, ye Mighty, and Despair—but it’s close.

At times over the years I have tried to reason my way toward a defense of my view as though some objective truth.

Pixie sticks? Come on. Maybe for horses. Even then, I assume PETA would protect them from such treatment.

Smarties? Must be the most ironically named candy of all time, given the consequence to one’s IQ from over-consumption. You might as well huff lead paint.

Swedish fish? Okay, I’ll concede that I have eaten one or two in my lifetime but by the third it tastes like someone has melted a battery and attributed the sensation to the Swedes as a cruel joke, probably in retaliation for Ikea.

This is all motivated reasoning, though. It is said that there is no accounting for taste, but this week I remembered how to account for my distaste. It has an origin story.

On Wednesday of this week, my eight-year-old son was snuggling me as I read the Chronicles of Narnia to him. We ended the chapter and he asked for a single piece of his Valentine’s candy. I agreed—it was after dinner after all and in that moment as I breathed in the smell of his hair and laughed at his laughter at whether Nikabrik would convince his comrades to assassinate the concussed Prince Caspian, he could have asked for permission to use the chainsaw and I might have granted it.

He quickly came back to me with his treat, but put it on my lap and asked me to open it. It was an uncommon one. I took it in my hands to open its multiple compartments and marveled as an acute memory ambushed me, first slowly then with a wallop. I immediately teared up. He took some steps back, unsure of what just happened.

“I haven’t seen Fun Dip in 35 years, since I was your age,” I said. “It was one of the last times I tried to eat sugar candy.”

On Wednesday, January 2, 1991, my father died at the age of 45. He was buried on Saturday, January 5, the same day that my mother and the man she married on Friday, December 21, 1990, had decided would be the last day for our family in Utah. We would move to Oklahoma in pursuit of my new stepfather’s third career. My grandfather planned the funeral so that we could attend. To waste no time, we drove our fully packed U-Haul and station wagon to the church. (I have written about some of the circumstances around my father’s life and death here and here.)

We didn’t attend the family dinner that my father’s fellow Latter-day Saints had arranged; we had to make it to New Mexico that night if we were to keep to my stepfather’s schedule. But as we stopped at the first gas station, Mom announced, against every historical experience, that each of the five kids in transit—my two eldest brothers were not with us—could choose a treat.

I wasn’t sure how long the offer would last, so I beelined for the Fun Dip. I had had one before at a birthday party and I agreed: this dip was indeed very fun. (For the uninitiated, Fun Dip consists of a hard sugar stick in one compartment that you lick and then dip into flavored sugar in another compartment; the sugar rush from the combination is severe. I’ve never done cocaine but imagine the effects are very similar.)

I could demolish sugar candy at the time, keyed by evolution to consume cheap carbs and by poverty to exploit plenty in the rare events that we encountered it.

This time, though, I almost vomited. I couldn’t finish it. It tasted all wrong, chemically imbalanced, giving off a whiff of death and tragedy. It was a crime of rankest order to throw food away in the Brown family in this era, never mind a rare treat such as Fun Dip. I shoved it into my coat pocket instead.

I have never been able to eat sugar candy again.

A few hours before we had gathered as extended family for a prayer and private viewing before my father’s funeral service. I found his waxen body, caked with cosmetics, deeply unnerving. I wanted little to do with this verisimilitude, this Not-Dad who looked enough like my Dad to unsettle my sense of just how much of Dad remained with us. I was mostly sure he was gone. But there he was, not gone but not here. I was eager for them to close the coffin while I held my proverbial pole at a safe ten-foot distance.

Before they did, we were gathered for a family eulogy. Among the only people who loved my father through his many dark days was Aunt Mary, my grandfather’s older sister. I knew from the few visits to Aunt Mary’s home with Dad that she was the family matriarch. That title plainly did not belong to my grandmother, who did not care for her son and gave the strong sense that she did not care much for anything—or anyone—connected to him, either.

Aunt Mary was different. She exuded love, care, responsibility, divinity. For that reason, I suspect, she was chosen to deliver the family eulogy. She described him with such tenderness, such protective passion, that I could tell that only his own father knew and loved him the way that Mary did. I loved my father fiercely and was shattered by his death. But I knew there were demons that stalked him. I could see and hear the knowing nods and knowing words about the life he might have lived in better circumstances. I knew that others placed an asterisk on the nice words they offered that day.

Mary rejected the asterisk. She loved him with a fierce intensity. It was more than materteral intimacy. It was a numinous expression that dismissed questions like fairness, justice, and desert—questions that loomed large over my father’s life and death—as she praised and buried a man who deserved the praise and required the burial.

At the end of the eulogy, with tears streaming down her cheeks, she bent over Dad’s coffin. “Goodbye, sweet Charlie,” she said, as she kissed his waxen face.

I elbowed my brother to make sure he saw what seemed to me a deeply transgressive act. He elbowed me back, angry that I had elbowed him but apparently unaware of what motivated it.

I was left to ponder that image alone. I reasoned like this. Mary the Aunt of Charlie was in my young mind similar to Mary the Mother of God. Was she even capable of a transgressive act? I didn’t think so. Handling this corpse was now within my Overton window. Perhaps enough of Dad remained after all.

As the adults in the room talked amongst themselves, I stole to the coffin, longing to connect just one more time. He was wearing a white tie, tightly knotted. This was the religious garb of ceremonial Mormonism, but I was ten years away from recognizing those clothes as such. I only thought he looked unusually dashing.

“Nice tie, Dad,” I said, as I patted his chest and smiled at the thought that he had, as he often did, really taken the time to put himself together that morning. Dad had a passion for the sartorial, right down to the tweed fedora that he left me—one of the only things he left me—when he died.

I smiled at that inside joke. Then my face crumpled, I dropped my head on the dead man’s chest, and wept.

That awful scene cuts my soul as I write it, but it lasted a second at most. My tears stopped quickly because my emotional burdens were now replaced by olfactory ones. I had never encountered that strange, swollen smell that now emanated from Dad, robbing me of the poignance of my goodbye, replacing it with the pungency of embalming fluids. Dad disappeared in a flash, replaced once again with Not-Dad. I was back to the verisimilitude.

These sensorial connections happened instantaneously, like the transmogrification of a boy into a superhero in an instant that the audience sees in slow motion. The waxen face, the tragic death, the endless hospital visits, the steady Grandpa, the aloof Grandma, the whirlwind romance, the hasty wedding, the cruel stepdad, the overpacked U-Haul, the beautiful Mary, the grieving Grandpa, the missing Grandma, the motley siblings, all of it together now had a smell worthy of their horrors.

I learned the word “formaldehyde”that day. It was an important word for me to know.

That’s what 1991 smelled like.

That was what Fun Dip tasted like.

In 2025, as I struggled to open the finnicky compartments of Fun Dip in shaking hands, my tears choked me and I opened up to my little boy.

“The last time I ate this was the day of my dad’s funeral. I was your age. I was so sad that day, and this candy seemed to concentrate all of my sadness in it. It even smelled the way my dad smelled in his coffin, which was a very gross smell, called formaldehyde, which is one of the chemicals they use to preserve people’s bodies after they die. I can smell it even now. I think that might be the reason I never could eat sugary candy.”

My son’s eyes, like saucers, absorbed the tale without blinking. I pulled him into my lap, Fun Dip in his hand, and cried silently again.

The next day I told this story to a dear friend who asked, innocently enough, how I was doing. Forty minutes later I understood a little better why I was so rocked by the sudden reappearance of Fun Dip. I realized that the feeling that overwhelmed me the day before was not grief for what I experienced in 1991 but a passionate intensity to protect my own boy from my past and various versions of his future.

I am many things. A scholar of the Fed. A powerlifter. A teacher of business school students. A Latter-day Saint. A guitarist.

But no identity matters more to me than father and husband. Success here is the meaning of my life. I want this for its own sake. I also want more than anything for my past not to be my children’s prologue. I ache for them to view what I have escaped with detachment. I don’t want them to have to traffic in those memories that, decades later, stalk me like a trophy hunter.

That night, the day after my sudden emotional confrontation with Fun Dip, I left for a business trip. I hadn’t had a chance to connect with my son again after that cuddle and was worried that I had not addressed those heavy ideas with appropriate sensitivity.

As I checked in with Nikki via phone, I asked to talk with my boy. “Did that story make you scared?” I asked him. “Did you feel like I didn’t want you to have Fun Dip? I don’t want you to feel scared when I talk about my childhood.”

We were on speakerphone. “It’s okay to feel scared,” my wife said. “We are here for you if you are scared. We just want to make sure we hear what you are feeling.”

“I wasn’t scared,” he said. “I still like Fun Dip. And I love all of your stories.”

I believed him. He does love my stories. They scare me a little. They do not scare him.

Weights shifted, some burdens displaced by others, my love steadily and unspeakably sweet, but there is no danger that my paternal love becomes frenzied or maudlin. I’m steadier and deeper than that. I know it and my boys know it.

I said goodnight then knelt in my hotel room to say my prayers. Teary and grateful that I get to be a dad to this boy and his brothers, a husband to my bride of two decades. Teary that I in fact do not know what my past will be to my boys’ future. Grateful that we are in a place where that unknown story can unfold before us all, together.

As I drifted to sleep, in that liminal space, I thought about what I want to do with each of my boys when I get home from this trip, wondered if Aunt Mary gagged on what she ate that day, and tried to remember what happened to the tweed hat that my dad wore to cover his balding head and if I could pull it off to cover mine now. My 14-year-old loves hats, you see, and I bet he’d like to see his grandpa’s hat.

Beautifully written with the heart as you always do when you delve into your past, linking it to the present and pondering the future. Nikki and the boys are very lucky to have you as husband and father. And I’m privileged to count you as a dear friend.