The Gift of Great Pumpkins

A small act with a large pumpkin from a kind church leader taught me how to see people as individuals.

Someone should write a novel called 84037, the zip code for Kaysville, Utah. It should be set in the early 1980s, when the Volcker Shock ripped through the country and caused unemployment to spike to almost 11%. It would be a story about strong Mormon communities, the Hoffman forgeries, the Reagan revolution, and (dys)functional families struggling to make sense of a changing world.

I can’t be the one to write it. It would have to be a memoir if I did. This was the world of my early childhood.

Dad’s wuthering and wandering professional life

My family moved to 84037 from Helena, Montana, in 1980. My father had graduated from Duke Law School in 1973, but only barely. During summers he delivered newspapers and worked as a short-order cook instead of working at law firms like the other Duke Law students. He spent more time at church planning the congregation’s musicals than he did on his exams. One of his classmates told me later that he couldn’t figure out why Dad, alone among the Latter-day Saint Duke students, spent so very much time accepting odd assignments from the local bishop instead of actually going to classes or preparing for exams.

My sense is that he was running away from the growing reality that his mind was not built for professional discipline. He was an intellectual virtuoso, but not a grind. He barely graduated at all and would not have finished if my mother hadn’t cobbled together some class notes, written an introduction, and submitted that sorry stack to a professor who reached out to her for Dad’s final required writing assignment. He graduated with a D average.

Dad had no job offers on graduation. His younger brother had to finagle him one at the Montana State Department of Agriculture, with which he had no other connections. Mom and Dad stayed in Montana for seven years.

The line between madness and genius is a thin one, the saying goes, and Dad walked that line clumsily. He did not enjoy work as a lawyer in a state agricultural bureaucracy in good times, so when the always-stalking mental demons would overwhelm him, he would sometimes disappear for days at a time. He was likely in the early throes of what may have been untreated bipolar disorder or perhaps a narcissistic personality disorder, though my mother tells me that everyone who knew him well had a different theory to try to make sense of his ailments. Toward the end, he became dissatisfied with his boss and his life and spent most of his time reading escapist and lurid romance novels to avoid the malaise and tedium that roiled within his broken mind. He was fired, with no professional alternative in sight.

A college classmate who knew more of the genius and less of the madness came to Dad with professional salvation. Come be a partner in our small Utah law firm, his friend said. You’ll be the sole partner in Ogden, in Northern Utah. The rest of us will be in Salt Lake.

Dad took the invitation. He had no relevant expertise so far as I have been able to tell, assessing his career many years after the fact. But Dad, the mad genius, was a dreamer and a romantic who imagined this toehold in Utah law to grow into a handhold of Utah politics and business that would culminate in becoming a US Senator or a wealthy magnate—which one he favored depended on his mood—and so he moved the family, then with five kids, to a split-level, 1400-square foot home in Kaysville, Utah.

The sixth child

My father’s law career didn’t take. In Utah, the lifetime of negotiated settlements with his mental illnesses finally unraveled. The Volcker recession didn’t help but Dad was unlikely to flourish under any circumstances. In the slow burn of their world, awash in increasing amounts of debt to everyone from friends and family to the IRS and the bank, Mom and Dad had two more kids, including me. Chaos reigned. The debts were squandered on trivia, consumed by Dad in binges, money disappearing in the moments after he received it. Finally, facing homelessness, Mom filed for divorce. My grandparents and the church stepped in to keep us off the streets.

The defining irony of my life is that I owe it to my parents’ inexplicable and indefensible decision to keep on bringing more children into this dizzying dysfunction. To make matters worse, I failed to thrive for the first twelve months of my life, victim to the spinal meningitis plague that swept the nation in the early 1980s. I survived with no obvious sequelae, although my meningitis did result in the regular line from an older sibling: “Imagine, Peter, what your life would be like if you weren’t [mentally disabled].” (In brackets because that wasn’t the term he used; the r-word was thrown around a lot those days.)

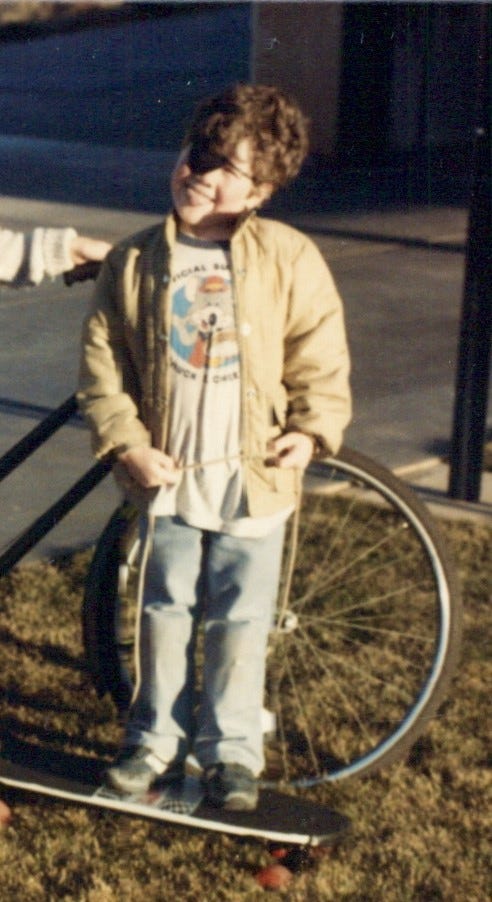

I was not in on the joke. I don’t remember how old I was when I realized I wasn’t mentally disabled, but it was probably 8 or 9. It didn’t help that I was born so severely cross-eyed that I required two invasive surgeries before I was three, which corrected my crossed eyes but did not stabilize my vision. One consequence was that I wore an eye patch (picture below) one year in an unsuccessful attempt to deliver to me some binocular depth perception. Three surgeries later in my adolescence and adulthood and I still can’t see straight.

My lights turned on as my parents’ marriage was ending. My first memories are of Dad and Mom or of Mom about Dad, probably within months of each other. In one, she is cuddling my baby sister as he leans tenderly to kiss them both hello. It is the only memory I have of them together in peace. In another, she insists that he can no longer waltz into their home given the pending divorce and he erupted in anger, turning a half-eaten apple into chunky sauce on the linoleum floor while we kids huddled in a corner. In the third, Mom turned off my favorite TV show - Today’s Special, I still recall - to tell me that Dad would not be living at our home any more.

These were years of acute grief at his loss and at his unreliability, themes I have explored again (and again (and again; sheesh, the Substacking some men will do to avoid therapy…)).

Meanwhile, for these and related reasons, life unfolded for me like a kind of off-Broadway free-form existentialist hellscape. I could not make sense of nearly anything about the world around me. Rules had to be explained many times and still I would not understand them. Norms were a total mystery. My grades in early elementary school were abysmal. There was talk of holding me back a year.

It wasn’t just presumed mental disability and terrible vision that constrained me. Everything around me seemed mysterious, threatening, overwhelming, dangerous. Just being the sixth of seven under-supervised children was a major health hazard. The line between play and brutality I experienced in that home and neighborhood shifts as I remember over time. I experienced heavy doses of both. For years I thought those stories were, if not quite hilarious, at least funny ones about scapegraces and mayhem that I assumed were common among my generation. Today they are sandpaper on my heart. I am not the judge of the bullies and abusers that roamed unimpeded in 84037, but sometimes the weighty memory of their actions push me off balance even now, forty years later.

For these reasons, a dominant theme of my early life was my attempts to escape. Sleeping underneath my bed. Running away from home. Many school days I would, even at age 6 or 7, wake up before 6am in the freezing Utah winters to go to school hours early so that I could swing alone with my thoughts. “If you are lonely when you are alone, you are in bad company,” Sartre wrote. I did not have that problem in 84037. Sartre’s existentialist hellscapes were my safe space.

The great Mormon welfare state

The Kaysville Fifth Ward, the name of our local congregation, was essentially coterminous with our neighborhood. There were a handful of non-Mormons among our neighbors. At least I think there were. There was no grand separation between church and geography in that neighborhood in the 1980s.

This fuzzy totality of faith and life meant that the status of the Mormon bishop in our town was something like a cross between a patron saint and a local celebrity. Bishop Tom Allen was both. We would see him presiding over this large flock each Sunday, but we would also clock when he came home from work in his small pickup truck, always with a wave and a megawatt smile. He was, at that point in my life, the most famous person I knew. But I didn’t really know him. As far as I could recall, at age 7 I had never spoken to the man. What would I, the sixth of seven in that chaotic time, even have to say to someone as important as him?

His celebrity-saint status is important context for what happened next. One day I was in the room I shared with two siblings and the family TV when my younger sister yelled my name in excitement as she shuffled down the stairs. The bishop was at the door. And he asked to see me.

That Bishop Allen wanted to see me did not compute as an electric current pulsed through my heart and head at my sister’s announcement. Our local hero had sometimes been to our home, but never to see me. I could not imagine what he could have in mind. There was no way it was good. I had internalized the very clear message that, in the ecosystem of 84037, I was a cipher, not very smart or interesting, probably disabled, not worth anyone’s trouble except for trouble. My eye patch sort of told that story for me.

Sudden individual attention may have been enough to terrify me for the few seconds between my summons and the revealed reason for it. There might also be more. I knew how dependent my family was on the Church. Through its network of collective farms, the church operated the world’s largest private welfare system. The church began experiments in collective farming early in its history, but by the 1980s, it was common practice for local congregations to staff these farms for purposes of providing food for those who could not afford it.

The Browns were such a family. During that season of divorce and poverty, the church welfare system took such care of us that we did not enter a grocery store for more than a year while Mom retrained to enter the work force full-time for the first time at age 40. The church—and Bishop Allen—carried us for those 18 months, ensuring that we were well fed and staving off homelessness.

I wonder now if I feared when Bishop Allen asked to see me if I had done something to disqualify us from his and the church’s life-saving interventions. I don’t know. All I remember was that I moved to the door as through a marshmallow. I had never been more nervous.

Peter Peter Pumpkin Sitter

Bishop Allen greeted me warmly, apparently unaware of how much turmoil his presence was causing me. “Come with me, Peter, I want to show you something,” he said, gesturing to the back of his pick-up truck. I could tell from his clothes and his truck that he had been at one of the farms.

In the back of his truck, I saw the largest pumpkin I had ever seen in my life.

“I found this gigantic pumpkin in the church farm and immediately thought of you,” he said, to my bewildered face. “So I got some people to load this into my truck and said ‘I am going to take this to Peter Brown in my ward as a present.’”

I had never had a conversation with the bishop that I could recall.

It wasn’t my birthday.

I had never thought about pumpkins in any meaningful sense before and certainly had no attachment to them.

Indeed, about the only association I had with pumpkins was the nursery rhyme that followed me everywhere, about the misogynistic feaster of pumpkins who imprisoned his wife in the shell of his pumpkin dinner so she wouldn’t leave him who just happened to share my name (side note: I’m 75% convinced Mother Goose was a gangster and a meth addict).

It wasn’t a positive association is my point, to the extent that there was any association at all.

I had then and have now no idea what could have possibly caused Bishop Allen to associate that pumpkin that day with me, the sixth child of a broken family whose whole existence at that point seemed to be anchored in surviving meningitis, predators, divorce, and eye patches.

Within a second, though, my nerves melted and I immediately fell deeply in love with that pumpkin. It was by far the most important thing I had ever owned. There was no close second.

Bishop Allen recruited my brothers to carry it into our home and parked it in my wall-less bedroom and family room, which was the same room.

I sat on that pumpkin for hours every day thereafter, indeed as though I was keeping something precious inside, fearful of its escape. I stayed that way until the pumpkin rotted away and made the house smell even worse than it already did. I remember as I was finally forced to carry it away in rotting pieces that it didn’t smell that bad to me.

Matching people to pumpkins

From 2017 to 2021 I served as a bishop in my local Pennsylvania congregation. Where my Utah ward covered a few residential streets and was too big for our chapel, our Pennsylvania congregation covers dozens of townships and is relatively small. But the concept of congregational community is as strong in the 2020s in Pennsylvania Mormonism as it was in 1980s Utah. Serving as a bishop remains the most meaningful and fulfilling work I have ever done outside of my role as a husband and father.

Throughout my time as bishop, I was mentored in fact and in memory by the people who had come before me, taking important lessons from each one. Bishop Bean, my bishop as a teenager in Oklahoma, taught me how to show people that you loved them and were rooting for them even as you helped them set high standards for themselves. Bishop Robinson, our bishop when our first sons were born in California, taught me how to build profound community in the presence of equally profound frictions, not by resolving those frictions but by learning from them.

Bishop Allen taught me how to match people to pumpkins. Many times as bishop I would get in my car and not quite know where I would go next until I showed up at a member’s home with a gift or a note or a conversation to say “this thing just made me think of you, I’m not sure why, but I hope you know what a special person you are.”

Bishop Allen didn’t save my parents’ marriage or my father’s life. He did not spare my childhood from abuse. He did not cure the social ills that gripped a country in the 1980s.

But that fall day in 1988, he did bring a struggling child a gigantic pumpkin, a seemingly inexplicable act that made me feel for those few weeks and in the decades thereafter a little less alone.

Powerful. Beautiful. Memorable. Thanks.

Thanks for sharing!