Fish stories

When I was nine years old, I moved halfway through the school year where a very good teacher read aloud Gary Paulsen's Hatchet. It went downhill from there.

At Dwight D. Eisenhower Elementary School in Norman, Oklahoma, there were two fourth-grade teachers named Mrs. Carlson. At some point in the years prior, someone had decided that the school would thrive better without walls. So it was that I, fresh from a hellacious few weeks that culminated in a midyear move from Utah to Oklahoma at nine years old, arrived in the middle of a large space with a lot of kids with heavy accents yelling for the attention of Mrs. Carlson, by which they meant two different people.

The Problem of Two Carlsons on the Open Floor Plan wasn’t my biggest problem, but only because my list of problems in 1991 was a long one. Everything about Oklahoma was strange to me. In my old town in Utah, the Mormon Church was coterminous with my neighborhood itself. In Oklahoma, by contrast, I was immediately labeled both a Mormon and a Satanist when one girl in the desk next to me loudly asserted that I believed that Jesus and Satan were brothers.1

Oklahoma was weird in other ways. There was no snow, for one, so my best path to social stardom, one I had utilized to extraordinary effect in Utah, was blocked. In that snowy wonderland, I was neighborhood-famous for building wild sledding obstacles and getting wicked nine-year-old air on my bright red racecar sled. No snow in Oklahoma meant no sled, no jumps, no wicked air, no social stardom.

There was an alternative path. More people in the Mrs Carlsons classes could name the starting lineup for the Dallas Cowboys2 than could name the Vice President of the United States. Football was life, and not just as spectators. The Carlsons’ Kids would square off, class against class, every single recess in a game of “touch” football that was, so far as I could tell, only different from legalized murder because we were too little to actually kill each other.

There was apparently another new kid, James Farris, who arrived (sensibly) on the first day of the year who dominated the gridiron so completely that he quickly became the most popular kid in school. James was a really nice kid, immediately showing me the ropes and encouraging me to follow his path.

It was immediately clear to me that such a path was impossible. I had probably held a football once before. I can’t remember. What I do know is that I was (and am) so visually impaired that I had no prospect of ever catching a football except in the most controlled of circumstances. I was born with such severe strabismus that my parents could not easily see my irises. Six eye surgeries later and even today I often have double vision and lack all stereoscopic depth perception.

When Carlson the First (that was my Carlson, we called her C1) and Carlson the Second (that was the other Carlson, we called her C2) squared off, James Farris got it in his head that he as quarterback should throw me the ball as often as possible. I caught it zero times. To James I blamed my eyes. I secretly feared it was because I was Mormon (the causal link wasn’t scientifically clear in my mind, but I was quick to blame any social barrier for many years on my minority religious status). It might have been the fact that although Oklahoma lacked winter snow, that wind that came sweeping down the plains was more like a horde of serial-killing banshees screaming with icy knives in their teeth.

Whatever it was, that was the first and last time I played Carlson ball. I don’t remember anyone ever excluding me exactly, but I do remember that everyone reached this conclusion separately, quietly, and with mutual appreciation that whatever mark I was to make in the fourth grade it would not be on that windswept football field. I watched from the swing set with other kids with glasses after that.

In my Utah elementary school, my teachers stopped doing read-alouds in second grade. That was baby stuff. C1 had a different pedagogical theory about the value of the exercise. When she announced it was time to gather in her reading “corner”—I cannot emphasize how utterly devoid of meaningful corners this vast warehouse-like elementary school actually was—it put me on my heels to see the football heroes like James Farris or his best friend Dax Cochrane plop down on their elbows and stomachs, chin in their hands. It would have surprised me less if they bragged that they never missed a Sesame Street if Count von Count was on. I had just watched these two carry C1’s team to glory. Now they looked like they were one juice box short of nap time.

Oklahoma made no sense to me, is what I am saying.

C1 knew her crowd, though. She read so many books to us that year. She had the voice of a 1920s radio announcer, never skipped the swear words, and gave every character a different accent. Except that the narrators, that is, all of whom had the same dewy Oklahoma accent that comes from the part of Georgia that is next to Lubbock, Texas. The whole scene was enchanting. Soon I was on my elbows too.

For her own reasons she never revealed, C1 specialized in survival fiction. I sometimes forgot that these were novels, so real was her verisimilitude. Books featuring the Hardy Boys and the Boxcar children, books like Trapped in Death Cave and Hatchet. Remembering these books now reminds me just how different pop cultural conceptions of parenting were in the 1980s. The parents in these books were certifiably non-present.

The most popular by far was Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet. To call Hatchet young-adult survivalist fiction doesn’t quite do it justice. Paulsen writes like a man who needs his young readers to know exactly what to do should they crash land a single prop plane in the wilds of Canada and have the good fortune to be (1) next to a lake, (2) with a plane full of meals-ready-to-eat, and — this part is very important — (3) in possession of a very good hatchet.

One iconic scene became the talk of the cafeteria. Brian, the main character, wants to fish. He has the lake, which has the fish, and he has a hatchet, which can sharpen a wooden spear. But, it turns out, fish in water play spatial games with refracted light. In his how-to fashion, Paulsen describes how Brian figures out that you have to aim beneath the fish to find its true place at the end of a spear. When Brian makes these connections of physics and mechanics, he starts feasting on fresh fish.

The braggadocio in the cafeteria among the fourth graders that day was extreme even for that self-assured crowd. James said he could definitely spear a fish if he were in Brian’s shoes. Dax said he had already done that very thing when he was on his last fishing trip. Before lunch was over half the class was describing the summers they had spent in the Northern Canadian wilderness where they had succeeded in franchising a local Chik-Fil-A by the time they were discovered by the Mounties.

I just watched in silence. That was how I spent most of the Oklahoma half of fourth grade. I was an alien in this strange culture. I also knew there was no way on God’s green earth that I would ever succeed at a task that oozed so much physicality and dexterity. My reasons were the same for all of my limitations. It was probably related to my strabismus or Mormonism. Or maybe it was the fact that we had just buried my dad in a distant place or that my mom had married just a few days before someone who was a stranger to us kids and barely better known to her.

In the Hall Park neighborhood of Norman, Oklahoma, at the end of Creighton Drive, there was a large water tower next door to the rented home where the five still-minor Brown kids were stacked two-or-three-to-a-room with the two newly-wed Wrights. A half mile from that house and that tower there was a pond we called a lake that smelled like it had been made as an apology for some oil project gone wrong. That isn’t a simile. I really think there was some active oil development there, which would not have made that place terribly unusual. Oklahoma is filled with abandoned oil projects.

In the first months after we moved to Oklahoma, before my tenth birthday, I would wander around that lake and those neighborhoods alone after school until it was dark. The water tower was easy to spot from anywhere I might wander, becoming my beacon and making sure I could never get completely lost.

I was always hunting for something. One time I found bleached bones on the ground that I brought home to do battle with my siblings, a femur versus a rib.3

On one such outing, I stumbled across a father and two sons who were fishing and frog harvesting. Frog hunting. Frogging? Whatever you do to find frogs and kill them.

The dead frogs were huge, tossed in a pile like exotic balled socks. The fish were tiny, but piled in a larger pile, looking like so many wood chips. I stood there taking in the scene, saying nothing.

I can’t remember how long before they noticed me and offered me part of their haul. At least I think they offered. I kept so much myself in those first Oklahoma months that I have a hard time imagining that I asked to partake. Same time, it seems like a weird thing for an adult to offer a random solo child a discarded tiny little fish that was retrieved from a pond that should have been managed by the EPA. Then again, these good people were fishing and frogging that very pond so perhaps offering part of their bounty was just downright neighborly of them.

I can’t remember. Nevertheless, within a few minutes of encountering that scene of (semi-) aquatic carnage, I had a fish in my hands, a spring in my step, and a story of explanation that was forming in my twisted little mind.

It was sunset when I walked into our home by the water tower and announced to my mother that she could pause dinner. I was providing it that day. I showed her my catch in triumph.

“I just speared this fish at the lake. C14 read us Hatchet in class about Brian who crash landed in a lake in Canada and who made a spear and learned that you have to aim under it to stab it so I found a stick and saw the fish and aimed under it and then here it was flopping on top of my stick, so I brought it home for us to eat.”

Let’s pause here to enumerate the many problems with this story on its face. First, the idea that I could see into that murky pond water is nonsense. I would have had better luck finding a fish in a barrel of oil such as I imagine predated the morass that we called The Lake. That water should probably be a Superfund site. For all I know it is.

Second, I just found a spear? I guess there were plenty of sticks around that wastewater, but seems like spear fishing requires a sharper point.

Third and most important, that fish was completely intact. No gaping spear hole in what might pass for its fillet. This fish clearly died of deoxygenation. Or maybe old age. Or maybe in protest for the humiliation I was in the middle of inflicting upon it. Point is that this fish and a fish spear very clearly never passed within a ZIP code of each other.

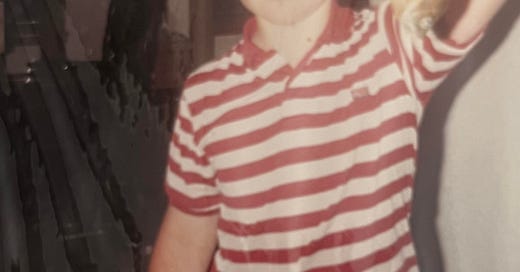

None of this mattered to Mom. She erupted in applause and laughter, dismissing any suggestion of skepticism from her mind. She loved the story and ran to get her camera. Recall that in 1991 taking a picture was a precious resource. She only took out her camera for special occasions. This was one such occasion.

She deboned the fish with love and chitchat and fried it up. I ate it. I don’t think anyone else did, for sheer lack of quantity if not lack of appetite. You would think it would have tasted like stolen valor, but it was delicious in my mouth. For those minutes and every time my mother retold that story—getting better and more detailed in every telling, she always did love a good story—I burst with pride. It is astonishing to me now that the massive lie beneath the story didn’t figure into my experience of it at all.

When I think of that spring day in 1991 from the comfort of the winter of 2025, I have a few theories for my mother’s enthusiastic credulity. She knew within days of her wedding that my stepfather was not a good addition to the family. She probably felt too that the tragic end to my father’s chaotic life probably did their children, his and hers, more good than bad. That’s a hard fact to ponder, and she fought hard to ensure that our memory of Dad, despite all the pain he inflicted on her, stayed precious to us. She felt the weight of her ragtag kids’ social malaise and wanted more than anything to lift it. She had heard the same things about Satanism and Mormonism from her Oklahoman Southern Baptist colleagues and told her to keep a stiff upper lip when we reported similar stories. And she, almost legally blind without her glasses in her own right, attended to my strabismus and my many surgeries with incredible care.

My 2025 theory, then, is that she knew I just dropped a whopper on our kitchen table. But she wanted to be co-author with me of a stabler, more venturesome world than 1991 could offer me from Norman, Oklahoma or the Wright-Browns, even if that meant we would enter together, hand-in-hand, a world that Gary Paulsen had made for someone else.

Eight years later my mother and I were sitting together on a couch in a different home, in a different town. My stepfather, her husband, was now physically and legally removed from the scene. And I was thriving. I never did learn to catch a football,5 but I bought a motorcycle and played guitar and bleached my hair and went to Warped Tour and grew sideburns and wore wild 1970s polyester clothes I would buy for $0.25 a bag on Thrifty Thursday at the local thrift shop.

All of this played to my advantage in mid-1990s Oklahoma. I even spoke with a slight accent. More Atlanta by way of Dallas, but I was fitting in nicely.

I also had my first epiphanal religious experience around that time. In Christian and Latter-day Saint theology is the idea that, through Jesus, we can become transfigured from sin to holiness through a process called “repentance.” To make it stick we need to follow that process which is full of rigor and hope. At age 17, I was navigating that process for the first time, under the tutelage of my very religious, very loving mother, with the assist of my local church leaders, some of the best people I would ever know, then or thereafter.

My “sins” were those of a regular 17 year old, but I found that once I started that process I wanted to take it everywhere I could remember, every time I had fallen short. Mom was my confessor. She was there for all of it. After a long time and lots of discussion we were near the end.6 I got up, feeling unburdened and extraordinary.

Then I remembered. “Mom, there’s one more. It’s a big one. You’re not going to like it. That time when I ‘speared’ a fish like in Hatchet? I lied. I made the entire thing up. I got it from a guy and his kids by that nasty lake in Hall Park. That scene from Hatchet was true, but I didn’t recreate it.”

She stared at me wide eyed as the whole horrid truth displaced the beautiful lie, word by word. I wasn’t initially sure she understood what I was saying, so ingrained was the experience in our shared narrative about my childhood. And then, at first quietly, Mom began to laugh. She couldn’t stop. By the end it was the loudest and longest I have ever heard her laugh. She didn’t say a word.

This week my 18-year-old niece found the picture my mother took that day. The fourth piece of evidence that it was all a lie are those eyes. That boy, you will agree, knew he was stomping about on some very thin ice.

Even so, I love that little boy and his lying eyes so much. At times when I remember that year I want to time travel just to hold him as I would my sons, now ranging in age from 5 to 16.

When my niece sent me the photo, though, I had a different thought. The school with no walls and too many Carlsons and all the rest of 1991 would pose their challenges, to be sure. They still do in their way.

But that boy who posed for that photo in media res was going to be all right.

I told her that I didn’t believe any such thing. My big brother told me later that night that it was a bit more complicated as far as he could recall.

This was the Troy Aikman, Jimmy Johnson era

I drew blood from my big sister in one bone fight; I’m glad she didn’t get gangrene from that. Whose bones they were and what they were doing in the middle of a field are still mysterious to me.

Mom knew the ways of the Two Carlsons and was hip to the local vernacular

I am telling you, even today you can’t be sure you have my attention my eyes are so bad

Footnote to self for future personal essay posts. These were sins about broken curfews, girlfriends she didn’t know about, times I had broken into an abandoned house, stealing our neighbor’s car when I was 13 and driving it to the junior high school to show off and almost got pulled over. It is a wonder I graduated high school without a criminal record, and my senior year had not yet even started (I got into so much trouble that year.)

We need to talk. I'll wear a white sport coat and a pink crustacean so you recognize me. Or it could be Jimmy Buffet.

Loved the whole story--down to your mom's laughing fit. I think you should frame that photo.